Introduction

This is our edition of the 1616-edition of Ambacht van Cupido by Daniel Heinsius. In this introduction, we have limited ourselves to the essentials.

About Daniël Heinsius

Daniël Heinsius was born in Ghent, a town in the southern Netherlands, in 1580.1 He lived there for only three years. His parents then fled from the Spanish Inquisition, and Heinsius was consequently raised and educated in the northern Republic. After his studies at the Franeker and Leiden universities (where his father wanted him to study law, while Heinsius himself was devoted to the classical literature and philosophy), Heinsius started working as a classicist in Leiden. As a professor, he edited many Latin and Greek works and composed Latin and Dutch poetry, almost right up to his death in 1655.

About the Ambacht van Cupido

First published in 1613 as sequal to Heinsius's Emblemata amatoria, the Ambacht van Cupido (The trade of cupid) was reprinted in 1615, 1616 and 1619, as part of an enlarged edition of Emblemata amatoria. A number of undated editions survived as well.2 For the edition of 1613 an unknown artist made new, oval picturae for Heinsius's first set of love emblems (allready printed in 1601 and 1608 and then titled Quaeris quid sit amor (see: [Titlepage]) and Emblemata amatoria (see: [Titlepage])). The picturae for the new collection named 'Ambacht van Cupido' resemble the style of Vaenius's Amorum emblemata, in the sense that they are also set in an oval shaped frame. The 1613-plates were again used for the 1615-edition. slightly restyled (given a retangle shape); by this time, the plates seem worn out. The engravings of the 1615-edition are of poor quality, and this could have been the reason the a new set of plates was made for the 1616-edition.

In the 1616-edition of the Ambacht van Cupido, digitized on this website, the two sets of love emblems were again combined and published in a larger volume with poetry by Heinsius titled the Nederduytsche poemata by Heinsius. In fact, the title 'Ambacht van Cupido' only appears on the titlepage of the 1615-edition of Heinsius' love emblems. It is used on this website to indicate the difference between the first and second set of love emblems by Heinsius. In the 1616-edition of the Nederduytsche poemata the section of love emblems is announced by a blank page with the title ’Emblemata Amatoria’ (see: [Titlepage]). The two collections of love emblems in this section of the book are separated by subtitles at each page, namely 'Ambacht van Cupido' and 'Emblemata van Minne'.

The 1616-edition of the Nederduytsche poemata was published by Willem Jansz.. For this occassion, Heinsius's poetry had been collected by his friend Petrus Scriverius (1576-1660), who had worked with Willem Jansz. before. In the preface to the book Aen den Leser (To the Reader), Scriverius explains that the 48 love emblems in the book are gathered from the 1613-edition of the Ambacht van Cupido as well as the 1601/1608-editions of Heinsius's Emblemata amatoria The first set of Heinsius's love emblems were, as Scriverius claims, really not the product of Heinsius's own imagination. They were gathered by a 'liefhebber' (lover of poetry) from the work of for instance Hadriaan de Ionge. 'Dan alsoo dit maer stomme beelden waeren, soo is de soet-vloeyende tong van onse Poëet daer toe geleent.' (Since these [=the images provided by De Ionghe and others] were nothing but silent images, Heinsius, our sweet-writing poet, lent his pen to them to provide them with words).

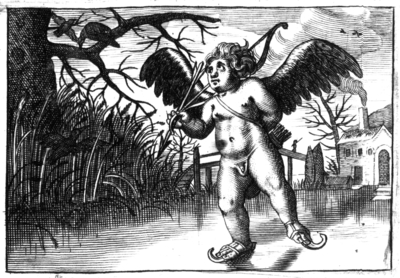

As said before, the picturae of Heinsius's first set of love emblems were remade in 1613 for the first collected edition of the Ambacht van Cupido and the Emblemata amatoria. The 1613 and 1616 picturae show more details in the background than the ones dating from 1601/1608. In emblem Cosi de ben amar porto tormento. [32], Ie reviēns de mōgréaux doulx lacqs qui me serrēt. [35], Ni mesme la mort. [43], Serò detrectat onus qui subijt. [45] and Perch'io stesso mi strinsi. [46] we now see a church in the background, where there was not one before in 1601/1608. In general, the church - and the morals in stands for - seems to have a more important role in the Ambacht van Cupido than it did in Emblemata amatoria. Allthough allready vagely visible in the background of some of the emblems of Emblemata amatoria, the church is a dominant element in emblem Pila mundus Amorum est. [1], Exitus in dubio est. [4], he1616012, Volvitur assidue. [14], Ferrum est quod amant. [17], Bulla favor. [21], Amor eruditus. [23] and Omnia conjungo. [24] in the Ambacht van Cupido. When we for instance look at the pictura of emblem Exitus in dubio est. [4]:

The Nederduitsche poemata, allthough reprinted only two or three times (in 1618 and 1621), had an enormuous influence on the development of Dutch literature. With the preface to the Quaeris quid sit amor? Heinsius had introduced the love emblem in the Netherlands (and Europe), but he also introduced another innovation, one that would have an impact outside the genre as well. In addressing the Aen de Joncvrouwen van Hollandt ("Maidens of Holland") Heinsius described in 1601 how Venus came to prosperous Holland in order to ask the poet to teach her son Dutch:

Self Venus van dit jaer (het is niet langh' gheleden)

Quam vroyelick en bly naer Hollandts rycke steden //

Den silveren dau quam //ghedruppelt hier en daer

Waer zy gingh ofte stondt //van haer schoon gouden haer

Zy wou dat haren zoon //by my wat zou Verkeeren //

Op dat hy onse spraeck van Hollandt mochte leeren/

[Venus herself this year (not long ago this was)

Came full of glad good cheer to Holland's prosperous towns.

Where'er she walked or stood, her lovely golden hair

Left scatterings of silver dewdrops here and there.

She came with a request, she said: that her young son

Could spend some time with me to learn our Holland tongue.

In this preface Heinsius justified the existence of Dutch-language poetry. Around 1600 it was taken for granted that he, as poeta doctus, would choose to express himself in (Neo-)Latin. By then opting for Dutch he became the emancipator of the Dutch language. He evidently felt some hesitation, however, for Quaeris quid sit amor? appeared in 1601 under a pseudonym. This can perhaps be explained by the subject matter of the volume, but the choice for the vernacular may have played a role as well. However that may be, by 1613 Heinsius had lost his timidity. In the Ambacht van Cupido, Heinsius did more than justify the existence of Dutch love emblems. Emblem In lubrico. [20] shows Cupid on ice-skates:

Cupid learns the game invented here in Holland,

He tries to walk on ice, he wears a pair of skates.

He's tied onto his feet the two sharp iron blades -

They'll keep him firm, he thinks, and steady on the water.

The ice is slippery, the blade against it, too,

It's easy to fall down, or even right straight through.

With wooing it's the same: those lacking well-honed skill

Will lose their footing fast, their love will come to nil.

Heinsius now claims that Cupid, during his stay in Holland, learned more than just the Dutch language. In passing, the god of love also mastered the skill of ice-skating. The Netherlanders - inventors of the "skating game" - taught him how to skate on their frozen canals. In the pictura we see a Dutch winter landscape and the typical wooden skates of the Low Countries. In gaining mastery over the slippery ice, this emblem suggests, Cupid also learned the fine points of the art of love. The situation in love is no different from that on the ice. Like skating, the game of love seems deceptively simple, but can only be learned by trial and error - by falling, getting up and trying again. Now that Cupid has learned from the Dutch experts how to stay on his feet on the ice, he can be considered truly accomplished in the art of love. Heinsius may have employed this positive image of the energetic, skilled Dutchman to counter the idea current elsewhere in Europe that in the cold, wet climate of the Netherlands only people of a crude, unrefined sort could thrive. The point here would then be that only in the Netherlands did Cupid truly learn the fine art of loving. By 1613, in Het ambacht van Cupido, Heinsius could speak with authority. With the addition of the 24 emblems of the Ambacht van Cupido to his collection of love emblems, Heinsius also went a step further in the realistic settings against which Cupid performs. The little god of love is pictured besides windmills, he skates on little Dutch canals, and he plays typical Dutch games.

Copy Used for this Edition

In preparing this edition of Ambacht van Cupido we have used the copy of the Nederduitsche poemata of the Utrecht University Library, shelf number AB: Moltzer 1 C 15.

Transcription

The full text has been transcribed and encoded using TEI mark-up, to allow for flexibility in presentation and non-destructive editorial enhancement of the text. The full project guidelines for transcription, editorial intervention and indexing of the text are available elsewhere on this site.

Literature

The full Emblem Project Utrecht bibliography may be accessed using the top menu of this window. A selection of literature relevant to the Ambacht van Cupido follows here.

Notes

, Bredero a.o., Thronus Cupidinis (facsimile)

, Bredero a.o., Thronus Cupidinis (facsimile) and Landwehr, Emblem and Fable Books

and Landwehr, Emblem and Fable Books

![[H O M E : Emblem Project Utrecht]](/static/images/rd-small.gif)