|

Hugo de Groot (1583-1645), known for his successful escape from the castle of Loevestein on March 22, 1621, was also

a

renowned scholar. In his book Inleidinge tot de Hollandsche Rechts-geleerdheid

(1631; roughly translates into "Introduction to the jurisprudence of Holland"), he concluded the aforementioned

medical evidence as follows:

Because women are colder and clammier by nature,

they are less adept at handling matters of the mind than men.

For that reason, men are born superior to women.

That is, the wise lead the not so wise.

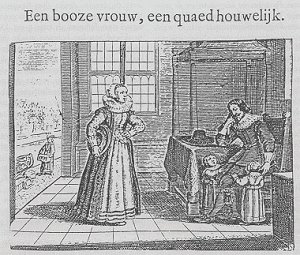

In a marriage, a woman should be kept under tutelage,

while the man acts as head and guardian.

Thus, a woman owes her husband obedience.

Yet, a man should never be allowed to hit his wife

or act cruelly towards her.

According to De Groot, women are 'kouder en vochtiger' [=cool and clammy], because they suffer from an excess of

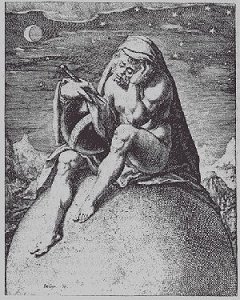

the elements 'earth' and 'water'. According to the aforementioned theory of the four cardinal humours, people

consisted of combinations of the four elements earth, water, air and fire. These elements corresponded with the

four bodily fluids black bile, phlegm, blood and yellow bile, respectively. Therefore, as maintained by this theory,

an excess of black bile and phlegm caused women to look pale and dull and be slow of comprehension.

|